Walk around Milborne Port and you will see a number of references to the Commonalty. Today this is a local charity that concentrates on providing housing to rent within the village. It has a small welfare fund to help villagers with unexpected expenses, and its sensible setting of business rents has enabled the village to keep shops that would otherwise be unprofitable. It also now owns the public toilets on the A30, and shares the upkeep costs with the Parish Council.

The organisation is a boon to everyone and has a long and interesting history. It began with the medieval guilds, continued through the religious upheavals of the Tudor era, and remained a charity in Victorian times, until during the 20th century it was streamlined into the charity we have today.

The Origin and Early History of the Commonalty

The Commonalty grew out of the early craft and merchant guilds that were established in medieval times. Milborne Port was an important town in Anglo Saxon times. The presence of a royal manor at Kingsbury and the important Minster of St John’s gave merchants and craftsmen ample opportunities to prosper. Following the Norman Conquest, the laws that had protected merchants and craftsmen were no longer upheld, so they banded together to form guilds. This enabled them to protect the rights of merchants and craftsmen against the powerful forces of the Church and the State, whose priorities were not always compatible with those of the businessmen of the town.

The guild made sure apprentices were properly trained; goods that were offered for sale were of good quality; and so on. (Many of these guilds still exist today, the headquarters of many of them still in London, and they form the basis of the Lord Mayor’s show each year.) The guild also acted as a guardian when necessary: if a member died or fell ill, the guild would take over his business and care for his family until a child was old enough to take over.

Milborne Port was run by its burgesses (the wealthiest of the craftsmen and traders) and the guild controlled the market, crucial to the prosperity of the town. By 1100 Milborne Port had a Guildhall; although the original building is gone, the Commonalty still meet in the upstairs room of the latest building to stand on the site, and the original doorway remains. This will be looked at later.

Milborne Port was rich, the burgesses did a good job, and this continued until 1348. This was the winter of the Black Death, and almost three quarters of the population of the town died! It is impossible to imagine a disaster on this scale. During the plague, people were dying so quickly that wills were not always relevant. The whole family might die, or only a couple of very young children be left, allowing the estate to fall prey to whoever claimed it. If a man was a member of the guild, one solution was to leave everything to the guild. It would care for any family left alive, seeing them housed and fed and the children suitably apprenticed. It is from this date that many of England’s guilds became wealthy.

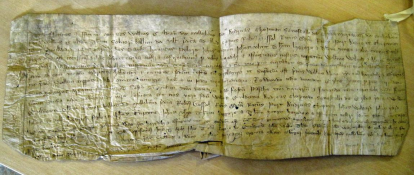

Milborne Port survived, but only just; it never regained its importance. This meant that our guild remained a single unit, not dividing into the specialist guilds as happened in larger towns, where each trade and craft had its own guild. One of the things the guild did was to pay for the upkeep and running of a chapel in the church where masses were said for the souls of departed guild members. However, the guild now owned a good deal of property, which it rented out, using the proceeds to support the families of its members who were in need. A deed exists from January 1382 recording that the guild was leasing ‘forever at annual rent of 2 silver pence’ a toft and land, that was at one time part of a tenement called Mariot, to William Walych and his wife, Alice. It is witnessed by John Toomer, Roger le Gulden, John Wyke, Thomas Edmund, and John Warderober. This deed also lists William Gulden and Andrew Chepman as stewards of the Merchant Guild. William Gulden was also a bailiff, as was Thomas Solver. Other members of the guild at this time were, Robert Gossell, Richard Odam, Richard Port, John Yard, John Woulward, John Taylour, Henry Pylere, John Cumpton, John Vhyt, Thomas Lyggere and Thomas Yonge.

In 1432 two borough bailiffs had control of the town’s seal. (This went missing for some years, but was found when Ron Hallett was doing some spring cleaning in his house on Wheathill Lane; he had been chairman of the Commonalty for many years before retiring in the 1980’s.) There is a stone replica of the seal over the front door of the Old Vicarage, so the seal was still in use when that was built in 1869.

The seal dates from the thirteenth century, and is made of silver. It was most likely cut from a stock blank with the pearled border already moulded. While the origin of the leopard, or lion passant, and the R have been lost, Milborne Port was a Royal Manor. The wording on the seal says Sigillum de Milborne Port (the seal of Milborne Port.) The seal would have been used on official documents, and was attached to the returns made to the sheriff of the results of parliamentary elections.

The two borough bailiffs were guild members and leased land from the borough. By this time the property listed in the ownership of the Merchant Guild was extensive; it included an orchard at Tont Well and another at Hempstonnes Well. There were tenements named Tolsey and La Brewerne, as well as the Olde Mill and the Guilde Halle Shop. This was probably what is now the cold room in the butchers shop on the High Street, since the Commonalty Charity still have the room above it. There was also land in Willibridge Close, Blyne Lane, and Fraternytie Close.

A parcel of wasteland at Toutewall had been taken over by William Toogoude and his wife Alice, and the Guild’s property included a common bakehouse.

John Jenes was a member of the Merchant Guild, and in 1496, he bequeathed them ‘one close next Powkebrook’. The lack of any standardisation of spelling means we cannot be certain where this was, but Powkebrook may later have become Puddlebrook, now Brook Street, where the Commonalty still own property.

Following the split from Rome in 1534, the biggest change to religious life was the dissolution of the monasteries. A while later all chantries, guilds and brotherhoods were also abolished, with their assets seized by the crown, something that was to have an effect on the Commonalty.

In February 1535, Ralph Pytt and his wife Joan agreed to give a brewhouse to the Merchant Guild, at the same time as they took out a lease from the guild on the estate at Yeld Hall for 4d per annum rent. Membership of the guild was costly, but the benefits included the chance to rent such prime property for a very small fee. The guild was careful however. Thomas Hallett, a tanner, and his wife and son made a similar deal in 1548; although he was a member of the guild, two other members were appointed to guarantee his payment of 11/6d per annum rent. By 1565 the Merchant Guild had become known as the Commonalty.

Apart from the dissolution of the monasteries, religion changed little during Henry VIII’s reign, but when he died, his son Edward VI changed church services and rituals to a much more Protestant form. This was revoked when his sister Mary tried to return England to the Catholic faith, but reinstated by Elizabeth 1 when she came to the throne in 1558. In 1571 William White became the vicar of Milborne Port. He had previously been the chaplain at Winchester College, and when he moved into the parish he must have been amazed to discover that the guild continued to support a chapel with a priest to pray for the souls of dead members. This had been illegal since 1547. It may not have been William White who complained, but an objection was lodged and guild property was confiscated while an enquiry was held.

The inquisition was taken at Milborne Port on 13 November 1571, in the presence of: Robert Jerrard, George Payne and John Mannynge who were the commissioners; with a jury of Robert Jerrard junior, James Wickham, Richard Everad, Nicholas Swanton, John Dore, Robert Warman, Stephen Gregorie, John Ponde, William Churchey, John Sampson, John Hewishe, John Whitinge, Stephen Newman, and Robert Chamberlayne.

The accusation was that the stewards of the ‘fraternity called the Commontie of Mylborne Porte’ had collected rents of 42/4d on certain properties., and that this had been used to maintain a presbytery, mass, and anniversary in a chapel called Chepmans Ylde (chapman means merchant, and ylde is an old spelling of guild) in the parish church, concealing the property from the monarch, who had only been given three small plots of land with a rent of 1/8d. The Dissolution of Chantries Act of 1547 meant all the properties should have been surrendered to the monarch, along with the 27/- worth of vestments and ecclesiastical ornaments in the church.

In modern terms, the guild was being accused of collecting rents worth 42/4d to maintain the priest and chapel, when these properties should have been forfeited to the crown. Instead the guild had only handed over three small plots of land with a rent of 1/8d. They had also failed to hand over 27/- worth of vestments and ecclesiastical ornaments from the church.

The Commonalty was lucky. The commissioners were businessmen and as the guild immediately agreed to stop maintaining the chapel and holding the mass, they allowed it to keep the property, and use the income for charity.

An inventory was made in 1585 and the following was found:

The deed of feoffment of the lands and tenements

A true copy of the Will and testament of John Jenes

One dede of exchange of Gonnes

A dede wytnessing the charter of King John with the rushe about the seale

An old evidence from Willm Gylde and other items from Wm Milborne & Ric Fry Stewards of the Coetie to Ralph Pyter of the Yeldhall

A grant from Wm Bishop and Reginald Sped Stewards to John Rawlyne of the horse myle

The town seale

For change in the law poured by Mr Jerrard

One roule of accounts in pohmet

An old rental in paper

A box of quitances

17 accounts

7 counter payres of leases

The Inventory is signed by William White

By 1596 a chamberlain had been appointed to assist the stewards in running the Commonalty Charity, using the rents to help the poor within the town. Milborne Port was a charitable town, with many individuals leaving bequests. These were all in addition to the charity doled out by the church, and that offered by the Commonalty. However, the Commonalty remembered its roots in the business community of the town and only offered help to those working people who lived within the old borough, or the dependants of these, be they children or the infirm.

The Guildhall

By 1100 Milborne Port had a Guildhall, and this still remains. It stands on the south side of the High Street and has a seventeenth century frontage, although the staircase is of an earlier style. The doorway has chevron moulding that appears in England from around 1050 to 1150.

The surround has been cut to suit the door, and we don’t know when this was done, but it probably happened following a fire in the building, when the front had to be rebuilt, and the carved stone was re-used to fit a new door.

In 1892, Mr Reynolds, gave a lecture to the Dorset Natural History Club on ‘Saxon Milborne.’ In it he claimed that the doorway was the original west doorway of the church, because the one incorporated in the 1867 rebuilding was fifteenth century, so he decided the original west doorway must have been moved to the Guildhall. Since there is no evidence to support this and few Anglo Saxon churches had a west door, it is now considered unlikely.

The door itself is fairly old, and has an interesting door plate. Maybe someone who is expert in these things could tell us more?

In the early days the downstairs room was a shop, usually let to a guild member to bring in a regular income, while the upstairs room was the actual Guildhall.

In 1854, when a new lock-up was needed, Sir William Medlycott agreed to pay the expenses of building one in the Guildhall. So the shop went but he paid a rent of 20/- a year to the Commonalty stewards for its use. This area now forms part of the butcher’s cold store.

The upstairs room is accessed by an early staircase which leads into the room still used as the Guildhall. As well as being the Guildhall, it was where people could pay money into the Milborne Port Penny Savings Bank. This was established in 1858 to ‘promote the welfare of the labouring classes.’ Open every Monday at the Guildhall from 7 to 8pm, workers could invest any amount from 1d, and were paid interest at 2½% on every 6/8d that remained in the bank for six months from 1 May or 1 November. When a deposit reached £10 it was to be transferred to the Sherborne Savings Bank.

The room was also used by the local magistrate to hear minor criminal cases until the court was established at Wincanton.

The high backed chair seen in the picture was used by the magistrate, and the table must have been constructed in the room since it is far too large to have been brought up the stairs or through the window.

Politics and the Commonalty

The Commonalty was a charity, but it still had the powers of the guild. This meant it held the town seal needed to make documents legal. It held the town weights needed to make sure no-one was cheated.

It also meant the two stewards of the Commonalty were the returning officers when elections took place. In January 1265, a parliament was called that included not only the Great Council, but also representatives from each county, and two burgesses from each town. The idea of including the burgesses was that as they paid the taxes, they should have some say where the money was spent. The two representatives would have been chosen from those willing to expend the time and money going to London by those entitled to vote. In Milborne Port this was the town officers, that is the nine capital bailiffs, their two deputies, and the two Commonalty stewards, and any inhabitants who paid scot and lot (town taxes). As parliament and society changed, this system carried on and towns like Milborne Port continued to send two representatives.

In 1660 Charles II was invited to become king, but it was on condition that he share power with parliament. Then in 1689 parliament invited William and Mary (she was Charles II’s daughter) to oust James, Charles’ younger brother, and take the throne. From then on although Britain was a monarchy, the real power resided in parliament. This became even more the case once the Georgians arrived, George I spoke little English and left the running of the country very much to parliament, which had a vested interest in protecting the rights of the landowners. Parliamentary seats were a valuable way of gaining support and influence, so wealthy men bought up manors such as those in Milborne Port, for the political power it gave them.

The nine capital bailiffs used to hold their land by royal right, but by the eighteenth century all these were owned by two families, and the office of bailiff was held in a strict rotation known as ‘The Wheel’.

It worked after a fashion. In 1661, Michael Malet and Francis Wyndham represented Milborne Port, although there had to be a second vote when William Milborne claimed to have won the seat. Many election results were contested, political chicanery was rife, and elections were rowdy. In Milborne Port the bailiffs were the returning officers, votes were cast publicly and the returning officers announced who had won, so they controlled the elections.

Although few people could vote, crowds would gather at election platforms to cheer or jeer, fight and drink. The restricted franchise meant that this was the only way many people could express their views. Those who did have a vote had to go to the returning officer and register it; since votes were cast in public, intimidation, or the purchase of votes by the wealthy was normal. Candidates were expected to donate generously to local charities and civic projects, and at the hustings they had to defend their record on keeping promises. Rival supporters, emboldened by the free beer that flowed copiously during campaigns, often disrupted the meetings. The freely flowing alcohol made for a riotous day, and the militia often had to be called out to restore order.

By the beginning of the 1800s the Medlycotts had sold their estate and political interest in Milborne Port to the Marquis of Anglesey. This made little difference since he, like them, was a Tory. However, a prominent Whig (the opposition party) Lord Darlington, tried to buy up enough of the town to take one or both parliamentary seats. This resulted in the two peers spending huge amounts of money in the town, but also generated many accusations of corruption.

At the election following the death of George III in 1820, the population of the town was 1,440 of whom just 111 had the right to vote, and both seats went to the Tories.

Thirty-seven special constables had been sworn in to prevent trouble at the election. The Whigs complained, saying they had evidence of bribery at Milborne Port, while Anglesey claimed that it was Lord Darlington’s party that used bribes. The claim and counter claim continued, and in November 1821 an open letter addressed to the inhabitants of Milborne Port and its vicinity suggested:

The Assembly room so much boasted of is no other than the upper storey of a wagon house, stable etc. The walls being 3½ feet from the floor with a shelving roof… The elegant and accomplished vituary who made the wares, the daughter of his bonded slaves. The music would have been passable but for the interruption by discordant notes from the piggery.

In 1832 the Reform Act was finally passed and Milborne Port lost its two MP’s as the new industrial towns of the midlands and north finally gained some representation. The Commonalty Stewards were no longer returning officers and a useful income was lost.

The Later History of the Commonalty

In 1836 William Phelps published The History and Antiquities of Somersetshire in which he explains that:

The town is goverened by the proprietors of nine bailiwicks or burgage tenures: and the persons to whom they were conveyed are called ‘Capital Bailiffs’; two of them preside annually at a court leet held in October. At this court two deputies or sub-bailiffs, and two stewards of the commonalty lands are appointed; also two constables, an ale taster, a searcher and sealer of leather, beside the parish officers.

The nine commonalty stewards are elected from the respectable householders in the borough paying scot and lot; two of them are annually chosen as reigning stewards, the others being assistants. The commonalty lands extend over various parts of the parish and produce an annual income of £52/9/4d which is divided by the commonalty stewards in alms to the poor on St Thomas’s day and Shrove Tuesday annually.

The Commonalty had now become a local charity that helped the ‘Second poor.’ These were people who were not in receipt of parish relief for whatever reason. Milborne Port was lucky in the administration of its charities. While some trustees may have been lazy, none were corrupt and they gradually they took over administration of the other village charities. Other places were not so lucky; in 1855 the law had to be changed to prevent trustees of charities disposing of land in ways that did not benefit the charity, since many trustees were selling off the lands to each other and pocketing the profits. The Commonalty had always rented out housing to bring in an income from which it helped the poor. Now it started building its own. In 1888 the terrace in North Street was built, and in 1898 after the jettied property on the corner of South Street burnt down, another new row of Commonalty housing was built.

However, not everyone was pleased by the actions of the Commonalty. On 20 January 1896 E J Ensor wrote to the Western Gazette to complain about the Commonalty Charity. He wanted to know why charity was denied to those in receipt of poor relief but given to those in more comfortable circumstances, and why Kingsbury Regis was excluded, with the charity being limited to old Borough. He pointed out that 29 years ago a man had died and left a family. He had been born at Stowell, but came to Milborne Port as an infant, yet his wife and family were still denied relief, even though the charity was given to men who had served a three year apprenticeship. He demanded to know what the authority for these rules was.

So the rules were clarified and published. They were:

Recipients must be persons belonging to the working classes who were born in Milborne Port, and who at the time of distribution live in the old borough. They must belong to one of the following classes:

1 married men or their widows with a child living, or if no child be at least 45 years of age

2 batchelors who are 50 or spinsters who are 45 years of age.

3 no person shall receive the charity who has within 6 weeks of the distribution received parochial relief.

4 application must be made to one of the trustees at least 15 days before the distribution of the charity

5 recipients who are able are expected to attend personally to receive the charity and the trustees reserve the right to refuse to pay it to any other person. The dole was to be distributed on Shrove Tuesday and Saint Thomas day (21 December).

The next major change for the Commonalty happened in 1894 when the Parish Council was set up. Until then, although it had lost some of its rights and powers, the Commonalty was still an important part of running the town, but it was not elected. Now this was to stop, and only elected councillors would have a say in decisions that affected the town, and the Commonalty would become just a charity. However, it is a fact of life that only a few people are prepared to give time and effort to run a town, and the records show that many of those who served on the parish council were the same people who also served the Commonalty.

Around 1906, the Commonalty exchanged much of the land they owned for houses owned by the Medlycotts. The Commonalty carried on with its work throughout the two world wars that caused such an upheaval in the first half of the twentieth century. It continued to let houses, shops and the remaining land, at realistic rents to townspeople.

The Commonalty Charity improved from 1980 from investments after the release of the rent charge, and its value was again increased in 1993 when the assets of the Horsey, Huxtable, and Winter charities were united with it. Richard Duckworth remembers that getting it all sorted took two days! It was then that the traditional award of the ‘dole’ on Shrove Tuesday and Saint Thomas day was stopped by the Charity Commissioners who said it was demeaning and not suitable for a charity today. This seems a shame, since many other places have been allowed to keep the tradition, including the Queen’s Maundy Money.

Today the Commonalty is a local charity that concentrates on providing housing to rent within the village. While preference is given to local families no-one is excluded. It also has a small welfare fund to help villagers with unexpected expenses, and some almshouses. Almshouses are strictly defined today, are regulated by the Charity Commission and are usually governed by locally recruited trustees. The majority of almshouse residents will be of retirement age, of limited financial means and living within the vicinity of an almshouse charity. Residents pay a weekly maintenance contribution which is similar to rent but different in law, and less than a commercial rate.

Information can be found on the Charity Commission’s Web Site. http://beta.charitycommission.gov.uk

THE COMMONALTY CHARITY LANDS

PROVIDE AFFORDABLE HOUSING TO LOCAL RESIDENTS ON LOW INCOMES Charity Number 235385

Date Registered 1964-08-13

Contact Name MRS H PINKAWA

Telephone 01963 250892

Address 26 WHEATHILL WAY, MILBORNE PORT, DT9 5HA Charity Commission Classifications

PROVIDES BUILDINGS/FACILITIES/OPEN SPACE, ACCOMMODATION/HOUSING

Governing Document

ANCIENT CHARITY – CUSTOMARY TRUSTS AS AMENDED BY SCHEME SEALED 19 SEPTEMBER 1996

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank many people who helped with the research for this essay, particularly Richard Duckworth who allowed me access to the Guildhall and its contents. I would also like to thank the trustees of the Commonalty, many of whom allowed me to interview them during my research. Thanks are also due to the staff at the Somerset Records Office, in Taunton, who were extremely helpful.

Dr Lesley Wray

Copyright © Milborne Port History & Heritage Group 2018